A house that turns into a small universe

If you want to understand the soul of Serbia, don’t start with a list of museums and monuments. Start with an ordinary house in which nothing that day happens “ordinarily”. On the wall, the icon of the family’s patron saint; on the table, a candle, wheat, and the scent of freshly baked ceremonial bread; in the hallway, a pile of coats; and from the kitchen, voices weaving together with the aroma of roast meat and Russian salad. Welcome to Slava – a family holiday unlike any other in the world.

Slava is the day when a family honors its patron saint, the protector of the home. It is a tradition characteristic primarily of Orthodox Serbs and passed down through generations, usually from father to son, like an invisible yet powerful family “identity card”.

Although deeply rooted in church customs, Slava is celebrated at home. On that day, the doors are wide open for relatives, friends, neighbors… As people say: “You don’t get invited to Slava – you simply come.” Whoever knows the date arrives, and the host is obliged to welcome everyone as an honored guest. With a smile, of course, and a table full of food.

The bread that tells a story: the ceremonial Slava loaf

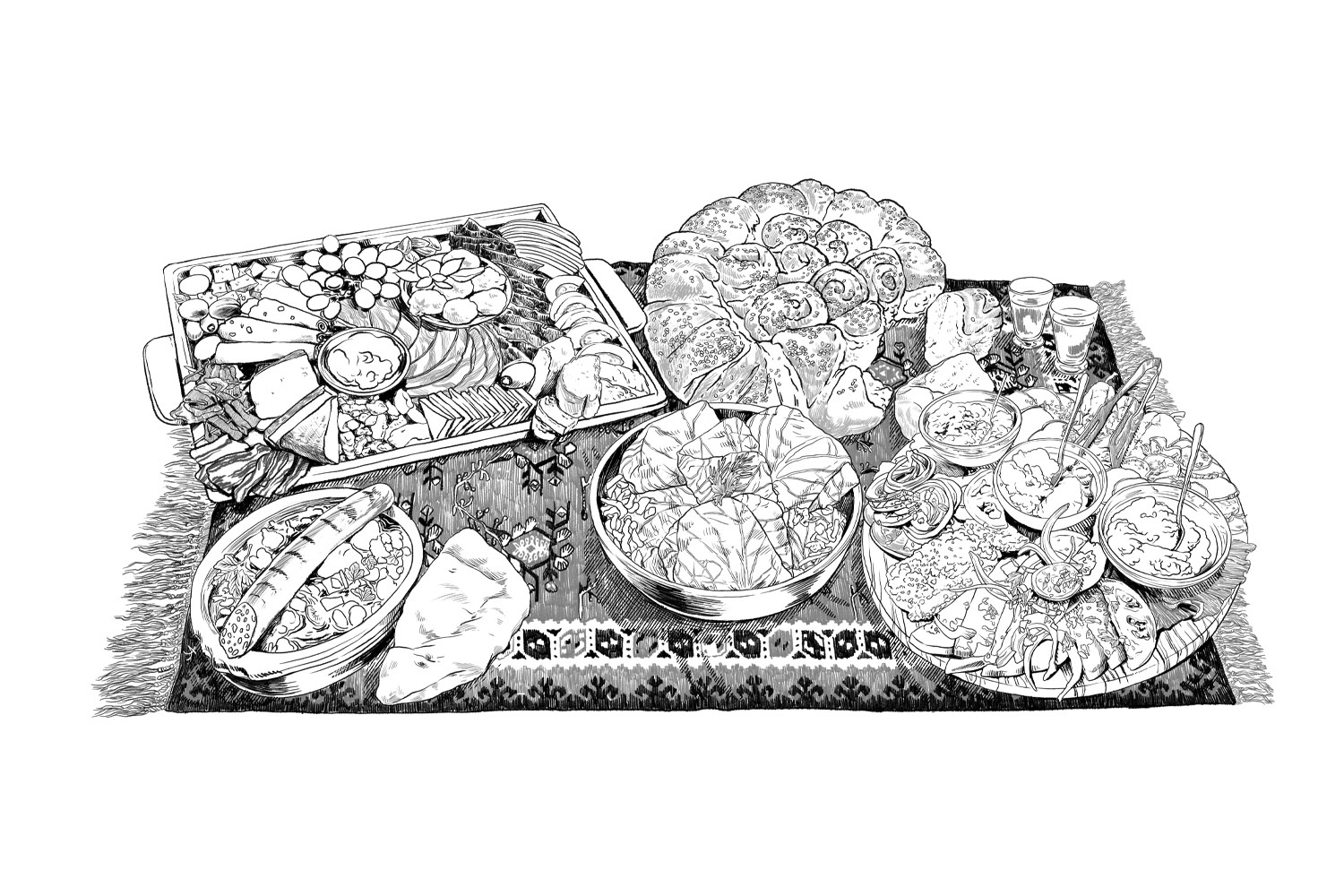

At the heart of this celebration is not a pile of gifts, but a single loaf of bread. The Slava loaf – a festive, richly decorated bread made from leavened dough – may be the best way to understand how gently Slava blends faith, tradition, and family intimacy.

The loaf is prepared the day before the celebration. In traditional households, the hostess kneads it after a prayer, with clean hands and special care, often using holy water. On top, the dough is shaped into a cross, grape clusters, wheat stalks, a dove, or the initials “IC XC NI KA” – small relief symbols of hope, life, and peace.

On the day of Slava, the loaf stands on the table next to a bowl of wheat (koljivo or žito, boiled wheat mixed with walnuts and sugar, in memory of ancestors) and a tall wax candle bearing the saint’s image. When the priest arrives, or when the family gathers in church, the loaf is poured with wine, then cut in the shape of a cross, turned, and broken jointly. That moment, when several hands hold the bread at once, is a tiny ritual of togetherness, as if the entire family breathes with the same lungs for an instant.

The symbolism is clear even to those witnessing it for the first time: the bread represents Christ’s body, the wine His blood, the wheat resurrection and eternal life, and the candle the light meant to illuminate the home throughout the year. Yet in practice, everything feels warm, intimate, gently ceremonial, and not at all “staged for tourists”. That is what makes Slava so special.

No matter how modest it may seem – one house, one family, one table – Slava has long surpassed the boundaries of a single nation. Because of its uniqueness and its role in preserving identity and family tradition, UNESCO inscribed Slava in 2014 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as a unique heritage of Serbia.

For a traveler who enters a home on the day of Slava for the first time, the initial impression is the feast. Depending on whether the day is a fasting day or not, the table may hold both fasting and non-fasting dishes: cured meats, cheeses, ajvar, stuffed cabbage, roasted meats, pies and gibanica, Russian and French salads, homemade pickles, cornbread, soups, cakes, and tortes. All of it accompanied by a glass of wine or rakija and a toast to the health of the hosts and guests.

Yet the essence of Slava lies not in “how much” food there is, but in “who” is gathered around the table. Slava is both a remembrance of ancestors and a promise to future generations that this home will always gather around the same saint and the same values. That is why many schools, towns, and even institutions have their own patron saint and their own Slava – from Belgrade’s Ascension Day to Saint Sava’s Day in schools.

For a guest from abroad, an invitation to Slava may well be the greatest compliment one can receive in Serbia. It means you are not “just a tourist”, but almost a member of the family. Your “ticket” is a smile, sincere curiosity, and, ideally, the readiness to say “živeli” at least once. If you also learn not to refuse another slice of cake, the host will likely consider you “one of ours” forever.

So, when you plan your journey through Serbia, alongside monasteries, mountains, and cities, leave room for something that cannot be mapped – an invitation to Slava. It is the moment when a travel itinerary turns into a family story, and you, from visitor, become a guest at a table that keeps memory, faith, and, of course, many irresistible delicacies.

UNESCO in the kitchen: a feast that unites guests and hosts

*Translation powered by AI